Continuity & Renaissance: Long Island Enters Its Second Generation

It occurs to me as I post the article on Long Island wine that I wrote last fall for Gilbert & Gaillard International now, that Long Island wine launched my career as a wine writer.

In 1999, I was working at the New York Times website www.nytoday.com (now defunct) and had put together a story about the winery scene in the Tri-State area: New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. Few people, even in the region, appreciated the long history and importance of the local wine industry at the time, and, arguably, still too few do so, today. New York State, where wines has been produced since colonial days, is home of the oldest bonded winery in the US, Brotherhood Winery (1839), located in the Hudson Valley. Moreover, in 1999, the state was second only to California in American wine production (today, it is third, after Washington State). Most production was upstate, around the Finger Lakes, 4 hours, plus, from NYC. Hudson Valley wineries were closer to city, but were more spread out from on another. And, besides, few vintners except for the brave/stubborn Michael and Yancey Migliore at Whitecliff Vineyard and the deep-pocketed (and also stubborn) John Dyson at Millbrook, were planting vinifera grapes – the Eurasian species responsible for the world’s great wine varieties. Long Island vineyards, two hours from the city, were almost purely vinifera, and, stylistically, very much what Euro-centric wine drinkers in New York City could appreciate.

So, off to Long Island wine country I went, focusing on the North Fork where most vineyards are located. I had visited plenty of other vineyards before – mostly in northern California were I attended university, and in France’s Rhone Valley and Languedoc – but these were the first vineyards/wineries I would be calling on as a writer.

My itinerary was ambitious: Macari, Paumonok, Pellegrini, Peconic Bay, Pindar, Corey Creek, Bedell, Pindar, and Lenz, all in a single day. The car, at $140/day, was the most expensive I had ever rented (even up until today), and being of limited means, I was not going to pay for a second day. By necessity – both for the reasons of schedule and the fatigue/impatience of my girlfriend at the time and two friends who joined us – most visits were quick: a rundown of what visitors could expect, and a quick taste of some of the wines. But, I lingered at three: Macari, Paumanok, and Lenz, compelled either by their stories, their personalities or the wines they made. Almost seventeen years later, these three wineries still compel me, though in subsequent visits to the region, I would come to add others, some passionately so.

Below is the article that appeared in Gilbert & Gaillard this past autumn, based three days of visits in June of 2015. Because of word limits, I couldn’t say in the magazine nearly as much as I would have liked. Some additional (still limited) comment and expansion follows the article.

Continuity & Renaissance: Long Island Enters Its Second Generation in Gilbert & Gaillard International, Autumn 2015

“Biodynamics does not guarantee you can make great wine. In some places, you are better off growing potatoes.” – Nicolas Joly, November, 2001.

By Jamal Rayyis

Thankfully Louisa and Alex Hargrave hadn’t heard of biodynamics in 1973 when they dug up a potato farm and planted a vineyard on the North Fork of Long Island, two hours northeast of New York City. Advised that Long Island had soils and a climate similar to winegrowing regions in France (which regions was never said), they planted classic varieties like Bordeaux’s Cabemet-Sauvignon, Burgundy’s Pinot noir, and the Loire’s Sauvignon blanc. A few local farmers predicted failure, and feared they might introduce new varieties of pests. Pioneers, the Hargraves had to leam by trial and error. But, fail they did not. Within a decade, over a dozen others joined them in the pursuit to make fine wine on Long Island. Forty-two years later, their courage inspired almost 60 others in the region.

SOME PRELIMINARIES

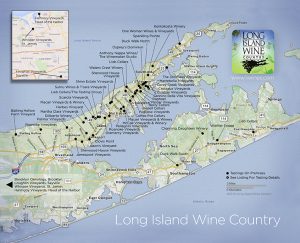

Long Island’s wine industry is centered in the northeastern portions of the island, including the North Fork to the west, which borders Long Island Sound, and the Hamptons, which borders the Atlantic. Peconic Bay separates the two. Surrounded by water, the region has a moderate maritime climate, a little cooler than Beaune in January, a little warmer in July. Summers are humid, but tempered by almost constant breezes. And, soils are diverse with glacial and maritime soils, sand, clay, granite and limestone. There are 1,200 hectares of vines planted here, primarily Merlot, Cabernet franc, Cabemet-Sauvignon and Pinot noir for reds, Chardonnay and Sauvignon blanc for whites. The young industry is now experimenting with novel varieties such as northern Italy’s Lagrein, Teroldego and Nebbiolo, Austria’s Blaufrankisch, Zweigelt and Grüner Veltliner and others.

Though thoroughly American in spirit, Long Island wines are stylistically more European than Californian. Indeed, the climate, topography,

and soil types closely resemble Bordeaux in parts. What’s remarkable about Long Island viticulture is that whether one picks early or late, grapes stay in balance. As Eric Frey, the California-trained winemaker at Lenz who has been in Long Island since the late 1980s, remarks with wonder: “In California, you have to work fast because of the heat. Here, I have a six-week window to pick Chardonnay, from mid-September ’til the end of October and get fruit with good ripeness and excellent acidity. The flavors will be different – from green apple to citrus to pear and tropical – but the balance is still there!” On the other hand, there is always the risk of hurricanes. Sandy, which devastated the East Coast, hit the end of harvest 2012.

WHAT’S TO COME

Long Island wine has entered its second generation. Many of the pioneers have either passed the reins over to their children, whilst some have passed away, leaving the legacy of their work to others. A few pioneers (the Hargraves, in 1999, among them) sold their wineries. At the start of the millennium, there was a rush of folks with big money and hubris, who built ostentatious wineries. Many departed after realizing the arrogance that made them successful in the world of business did not work in the wine industry, especially one that will essentially stay at boutique scale, with annual production at under 50,000 hectoliters. Several winemakers on the Island see the future as one of smaller vineyards, smaller wineries and more focus on quality than tour bus visitors.

A FEW OF THE REGION’S EXCELLENT WINEMAKERS

Anthony Nappa – Trained in New Zealand, Anthony Nappa makes wine at Raphael, which was founded in 1996 on the Bordeaux château model. Until Nappa arrived in 2013, the wine was underwhelming, but Raphael’s owners saw his talent and gave him the latitude to do things his way, including making his own, eponymous wine on the property. While Raphael remains classic, Nappa’s own wine can be singular and esoteric, though totally balanced. He and his wife Sarah sell the wines at their Anthony Nappa Winemaker Studio, which also supports other boutique winemakers, providing them a venue to offer their unique wines.

Channing Daughters – A visit to the Hampton’s Channing Daughters is dizzying. Winemaker Christopher Tracy is a fast talker, necessarily, so he can describe the over 30 wines he makes. For another, Channing Daughters, more than any other winery in the area, is fervently dedicated to showcasing Long Island’s diversity, making an array of wines from grapes like Blaufrankisch, Lagrein and Ribolla gialla. Tracy is thrilled by what is possible on Long Island. “We aren’t dogmatic, we try different things so long as we keep two ideas in focus: reflection of place, and deliciousness.”

Lenz – Established in 1978, Lenz has some the region’s oldest vines, including some of the oldest Merlot in the United States, which wasn’t embraced by California until the mid-1980s. Winemaker Eric Prey, a self-described curmudgeon, is no nonsense and maintains very high standards, tutoring a number of emerging producers.

Macari – In 1999, during my first visit to the North Fork, Joe Macari introduced me to biodynamics, changing the way I looked at wine. One of the largest landowners in the North Forth, the Macaris never went fully biodynamic, but they maintain its principles of biodiversity on their property that includes 80 hectares of vines. Joe and wife Alexandra’s son Joey is now in charge of viticulture. Daughter Gabrielle handles marketing. Their large range of wines is both exciting and excellent.

Paumanok – Paumanok is the gold standard for the region’s quality. What started in 1983 as a sort of hobby became by the early 1990s, a successful quality-driven business, carefully run by Charles and Ursula Massoud. The wines, made from classic European varieties, have a rare precision to them. Their Chenin blanc is unique to the region, and among the best outside the Loire Valley. Today, the Massoud’s sons have taken charge, Kareem as winemaker, Nabeel as vineyard manager, and Salim as an administrative manager. As others experiment, Paumanok is a comerstone to assure the region’s success into the future.

Shinn Vineyards – Barbara Shinn and David Page are hard-working romantics. Successful restaurateurs in Manhattan, they always emphasized consuming local, wholesome products. They planted their vineyard at the end of the 1990s, devoting more energy to biodynamic production, difficult in Long Island’s humid climate, than anyone. The biodynamic process hasn’t been entirely successful, but they are drivers in a regional move toward sustainability. David also is the only licensed winery distiller in the region. Unrelated, the inn they run at the property is wonderful.

Wölffer Estate – Part of the Hamptons’ scene since financier Christian Wölffer founded it in 1988, Wölffer Estate has focused on quality from the start, both in its wines and the visitor experience. “We have to be aware that we are a tourist area, and provide for it,” says Roman Roth, winemaker since 1992. Appropriately, 70% of the 520,000 bottles made are rosé, which happens to be among the finest in the United States. The Bordeaux-styled reds are excellent. Wölffer’s children took over upon his passing in 2008 and made Roth a partner.

Other wineries with stories to tell: Jamesport, Mattebella, McCall, Old Field Cellars, One Woman Wines, Pellegrini Vineyards, Roanoke Vineyards, Sannino Bello, Southold Farm + Cellar, Sparkling Pointe.

Fin

A few extra words (and some of those other stories to tell):

The pressures that Long Island wineries face from both, ironically, creeping development and land use-restrictions is felt, perhaps most directly in the township of Southold. I was able to spend a bit of time at two Southold wineries under pressure: Christian Baiz and Rosamond Phelps at The Old Field Vineyard on the eastern edge of the township, up to the waters of Peconic Bay, and Regan Meador Southold Farm + Cellar, inland, at a higher elevation. The property of each is about the same size, 22 acres, 10 under vine for the former, 24, 9 under vine for the latter. Yet, each of these wineries deal with distinctly different issues: Chris Baiz represents the fourth generation of his family farming the property his great grandmother acquired at the end of World War I. Regan and his wife Carey are farming a property that was derelict when they bought it in 2012. Clearly, the need to buy land in 2012 necessitates a different economic approach than working property that was largely inherited.

Baiz, who, while attending to some aspects of the farm, had a career as mining engineer before returning to the farm full time. It is easy to see why he returned The property is one of the loveliest in all of Long Island, a true reflection of gentile quaintness the Old Field name evokes, verdant, with tall, old trees and wild growth surrounding the vineyards, and beautiful Peconic Bay shimmering just beside. At present, his wife Ros is in charge of winemaking and daughter Perry, who studied environmental biology, manages the vineyards. Foremost in Baiz family’s mind is sustainability – not just in an environmental sense (and they do make a point of farmi ng sustainably) – but economically in the long term, that is, into future generations, as well. According to Chris Baiz, the US Department of Agriculture has determined that the North Fork is the most expensive agricultural land in North America. It isn’t easy to get financing for operations, so overhead has to be kept low and operations small and lean. It is vital to attract to the winery people who will not simply taste and maybe walk away with a bottle, but will linger, feel invested in the experience, and not only buy a case, but also, will return for more. Ninety-eight percent of Old Field sales are at the winery – for full retail price – rather than the far lower margins that would be necessary for wines sold through wholesale distributors and retail shops. Space rentals, especially for weddings – are an important source of income as well, as they are for many other wineries on Long Island, as well as in most other American wineries. Production facilities are simple, with 500 cases – red, mostly – made at the winery, plus others, whites, made at Lenz winery down the road. How are the wines? I can’t really say. Other than a merlot of these I tasted three years ago, I don’t have other experience with the wine. Despite the generosity of time and information – plus a wonderful golf-cart drive through the vineyards and to the edge of the bay – no bottles were opened for tasting. My visit was to understand the region rather than comment on the wines, so I didn’t really mind. All I can say, is that I hope I’ll have a chance to taste in the not so distant future.

ng sustainably) – but economically in the long term, that is, into future generations, as well. According to Chris Baiz, the US Department of Agriculture has determined that the North Fork is the most expensive agricultural land in North America. It isn’t easy to get financing for operations, so overhead has to be kept low and operations small and lean. It is vital to attract to the winery people who will not simply taste and maybe walk away with a bottle, but will linger, feel invested in the experience, and not only buy a case, but also, will return for more. Ninety-eight percent of Old Field sales are at the winery – for full retail price – rather than the far lower margins that would be necessary for wines sold through wholesale distributors and retail shops. Space rentals, especially for weddings – are an important source of income as well, as they are for many other wineries on Long Island, as well as in most other American wineries. Production facilities are simple, with 500 cases – red, mostly – made at the winery, plus others, whites, made at Lenz winery down the road. How are the wines? I can’t really say. Other than a merlot of these I tasted three years ago, I don’t have other experience with the wine. Despite the generosity of time and information – plus a wonderful golf-cart drive through the vineyards and to the edge of the bay – no bottles were opened for tasting. My visit was to understand the region rather than comment on the wines, so I didn’t really mind. All I can say, is that I hope I’ll have a chance to taste in the not so distant future.

One way landowners can get financing is to sell their development rights, transferring them to other parties for future use. With the right to develop land for housing or tourism purposes limited by a desire to maintain the region’s agricultural legacy, the actual right to do more than farm is valuable. And, it is easy for cash-strapped farmers to be seduced by the possibility of selling a commodity – development rights – that they don’t think they’ll ever use. If you have no intention of building on your farm/vineyard, then, who cares if development rights are ceded to others? Unfortunately, things can changes. As Chris Baiz cautions, ‘Selling development rights is okay for the first generation, but there is no equity for the second, since their sale devalues the property. It doesn’t work for the future.”

Regan and Corey Meador, who bought a derelict farm in 2012, do not have development rights, or, anyway, very limited ones. In their 30s, they left their NYC advertising careers (though Corey still does that part time), for the relatively slower, certainly more connected-to-the-earth life of winegrowers. Being new to the industry, and planting a vineyard anew, afforded certain advantages, especially the ability to experiment with grape varieties that the region wasn’t already known for, and to make wines of a type, and possibly, quality beyond what had been done before. Like Christopher Tracy at Channing Daughters, northern Italian grapes like Teroldego Rotiliano, Lagrein, and Moscato giallo have been planted, as well as Cabernet franc, Merlot, Petit verdot, Malbec, and Syrah. The latter has been an under-performer and will likely be grafted over to Blaufrankisch. And, also like Tracy (and, it should be added, Anthony Nappa), Meador doesn’t follow the ‘traditional’ route to winemaking – working outside the model of classic Bordeaux or Burgundy inspired wines – to experiment with carbonic maceration, carbonation, extended skin contact and fermentation for white wines, etc. In other words, he is one of the cool kids. Meador also has a different vision of who he wants to buy his wines. While no one on Long Island would be unhappy selling his/her wines outside the region (beyond, even New York City), the dominant model is tasting room sales, with all the advantages of full profit margins. A large tourist industry – much of it moneyed – almost guarantees, in principle (with several counter examples), a certain level of success. The model for Southold Farm is distinctly toward distribution, and indeed, its wines are distributed in more states – even on the West Coast – that possibly any other winery in the region. That is a good thing, since soon after my visit last June, the Southold town board ordered the closure of the Meador’s tasting room and forbade the construction of a winery on the property. The reason? Improperly understood development rights with a dose of nimbyism. That is, a neighbor complained about traffic to an unmarked winery. The issue has been covered in the press, here and here and other places. And, while the Meadors didn’t plan to rely solely on tasting room sales, to do without, especially in a heavily touristed region, puts the whole enterprise into serious question. As of this writing, no final decisions have been made. The winery’s website says they are doing only online sales, though no wines are being offered. It’s a sad tale, born out of the myopia of local officials who are, unable to see that the long-term viability of agriculture in the North Fork depends on innovators such as Meador, neighbors who think they can maintain some Waldenian ideal by simply rejecting anything new, and, to be fair, probably some naïvité on the part of the Meadors. Good intentions and leaps of faith often cannot overcome small minded fear, not without deep pockets in any case.

Some additional notes on wines

Of all the wines tasted both during my visits and subsequently, those of Anthony Nappa struck me more profoundly.

He shares, with Chris Tracy and Regan Meador, a unique spirit of experimentation that, I think, is necessary for Long Island to become a region recognized for its wines rather than a region recognized for being a lovely place to visit that also happens to make wines. (This isn’t to say that the classical wines are not also essential for this recognition to take place. The region would suffer tremendously if it didn’t have the likes of the Massouds at Paumanok, Roth at Wolffer, Fry at Lenz, and the Macaris at, well, Macari, as well as several others, all of whom make exemplary wines, year in and year out)

Fermenting white grapes on the skins – creating ‘orange’ wines is in vogue for a number of avant garde winemakers – and a fad of sorts for a few wine drinkers (generally, I really like them), Anthony Nappa, among them. But, he thinks beyond treating white grapes as red. Take,  for example, his Spezia Gewurztraminer 2013, which is made from grapes, 40% fermented on the skins and 60% fermented through carbonic maceration, all pressed together. The wine is dry, but also luscious in texture, full of spice, smoke, orange zest and lemon oil flavors, a touch tannic, and simply delicious. Reminisce 2013, a Sauvignon blanc made from grapes macerated on the skins for 3 days before fermentation, is savory, with flavors of fresh pressed olive oil, lemon and wild herbs. Frizzante, a sparkler made in the Col Fondo style – is an old school Prosecco styled wine from Pinot noir, Riesling, and Gewurztraminer, that undergoes a secondary fermentation in bottle (unlike the overwhelming majority of Prosecchi today, which do their secondary fermentation in tank), without disgorgement. It is brilliantly fresh, with floral and stone fruit flavors and full of energy. Reds are more “traditional” but show Nappa’s unique hand. La Strega Malbec has a rustic edge to it that reminds me of a vino di contadino I had three years ago in the hills above the Amalfi coast (poured from a re-purposed Prosecco bottle), full of tasty tart cherry flavors and snappy acidity. A tank sample of the 2014 Ripasso, made from Merlot that was macerated, post fermentation (‘re-passed’) over Petit verdot and Malbec skins (alla the wines of the Veneto) for six months, evoked dark, wild berries and amarena cherries, black olives, and dry leaves. While Nappa makes his wine at Raphael winery, that is, his day job, they are available at the Anthony Nappa Winemaking Studio, which also features the personal wines made by others who, like Nappa, are lead winemakers at larger wineries. Fortunately, Nappa’s wines are also in distribution. As coincidence would have it, I visited the studio at the same time as Amy Ezrin of Massanois Imports, who, similarly impressed, agreed to take the wines into their New York and New Jersey distribution portfolio.

for example, his Spezia Gewurztraminer 2013, which is made from grapes, 40% fermented on the skins and 60% fermented through carbonic maceration, all pressed together. The wine is dry, but also luscious in texture, full of spice, smoke, orange zest and lemon oil flavors, a touch tannic, and simply delicious. Reminisce 2013, a Sauvignon blanc made from grapes macerated on the skins for 3 days before fermentation, is savory, with flavors of fresh pressed olive oil, lemon and wild herbs. Frizzante, a sparkler made in the Col Fondo style – is an old school Prosecco styled wine from Pinot noir, Riesling, and Gewurztraminer, that undergoes a secondary fermentation in bottle (unlike the overwhelming majority of Prosecchi today, which do their secondary fermentation in tank), without disgorgement. It is brilliantly fresh, with floral and stone fruit flavors and full of energy. Reds are more “traditional” but show Nappa’s unique hand. La Strega Malbec has a rustic edge to it that reminds me of a vino di contadino I had three years ago in the hills above the Amalfi coast (poured from a re-purposed Prosecco bottle), full of tasty tart cherry flavors and snappy acidity. A tank sample of the 2014 Ripasso, made from Merlot that was macerated, post fermentation (‘re-passed’) over Petit verdot and Malbec skins (alla the wines of the Veneto) for six months, evoked dark, wild berries and amarena cherries, black olives, and dry leaves. While Nappa makes his wine at Raphael winery, that is, his day job, they are available at the Anthony Nappa Winemaking Studio, which also features the personal wines made by others who, like Nappa, are lead winemakers at larger wineries. Fortunately, Nappa’s wines are also in distribution. As coincidence would have it, I visited the studio at the same time as Amy Ezrin of Massanois Imports, who, similarly impressed, agreed to take the wines into their New York and New Jersey distribution portfolio.

————————————-

The premise of the original Gilbert & Gaillard article above was the regeneration of the Long Island wine industry, with pioneers passing their business to their children, or young winemakers arriving continue the work started by others. Space limitations prevented me from speaking about everyone I would have liked, but it’s necessary to make mention of Zander

Hargrave, son of Louise and Alex Hargrave, the region’s founders. Louise and Alex sold their winery in 1999, effectively retiring from the business. Zander, who grew up in the vineyards and around the winery, did his own thing, leaving the region to study history, and earning a master’s degree in education. No doubt, a career as an academic was his for the taking. Yet, something, call it a genetic flaw, drew him back to region to make wine. While he didn’t have his family winery to go back to, he nonetheless took the opportunity to return in 2011, first as an assistant winemaker at Peconic Bay winery (since closed) and lately, as head winemaker at one of the other pioneering wineries in the region, Pellegrini. Though he grew up in the industry, and surely saw the struggles required, 38 year old Hargrave shows the enthusiasm who a kid who just discovered Christmas for the first time. He is deeply appreciative and proud of what his parent accomplished, noting, especially, that they had so little to work with from the start – little knowledge and few choices in terms of grape variety. “But, now, we can do so much. We know we can make excellent Merlot and Chardonnay – even world class, but, it will take time to dial into to all the variables, what works best for us.” For the moment, I judge Pellegrini wines – as I have for a long time – to be solid, well-made, nicely balanced, but not transcendent. Starting just before the 2014, Hargrave hasn’t yet had the opportunity to make fully his mark on the wines. Given his enthusiasm, both for his work, as well as the new generation of pioneering winemakers utilizing different grape varieties and winemaking techniques, there is no doubt that Hargrave is someone to watch in near future.

———————————————-

As stated in above in the Gilbert & Gaillard article, Long Island is now home to some 60 wineries. Or, how shall I put it?: wine brands. Because of their small size, many wineries have their wines made at other facilities, and, truth be told, by wine making consultants. In fact, as much as 70% of Long Island wines are made by 5 different people. Eric Fry of Lenz, Roman Roth of Wolfer, and Giles Martin of sparkling wine specialist Sparkling Pointe (a subject for a future article), are prominent in this regard. To be sure, winery owners who employ their expertise, might add their own personality into the final wine. The wines are good, sometimes exemplary, but there is an inevitable sameness to many of them. Then again, Michel Rolland makes wines throughout the world – and, while those might be accused of sameness, too – one cannot say many of them cannot be exciting wines, besides. [Exciting or not, while I appreciate what Rolland does, I am not a fan of his style].

Fortunately, there is more than enough dynamism on Long Island to assure that.

No Comment